Scramble for supremacy: the world in 2024

After a turbulent economic & geopolitical year, intense competition within and between economies will become even more pronounced in 2024.

At the end of another turbulent year, I have been thinking about what firms, investors, and governments should be positioning for in 2024. Together with Mike O’Sullivan (long-time collaborator and Landfall Strategy Group Senior Advisor), I have prepared a paper on the dynamics that we expect will shape the year ahead. The note below summarises the key points in this paper.

Do get in touch (david.skilling@landfallstrategy.com) if you would like to arrange a briefing and to access the full paper.

If this has been forwarded to you, please do subscribe to receive my weekly insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics. Information on free and paid subscriptions is available here, including group & institutional subscriptions.

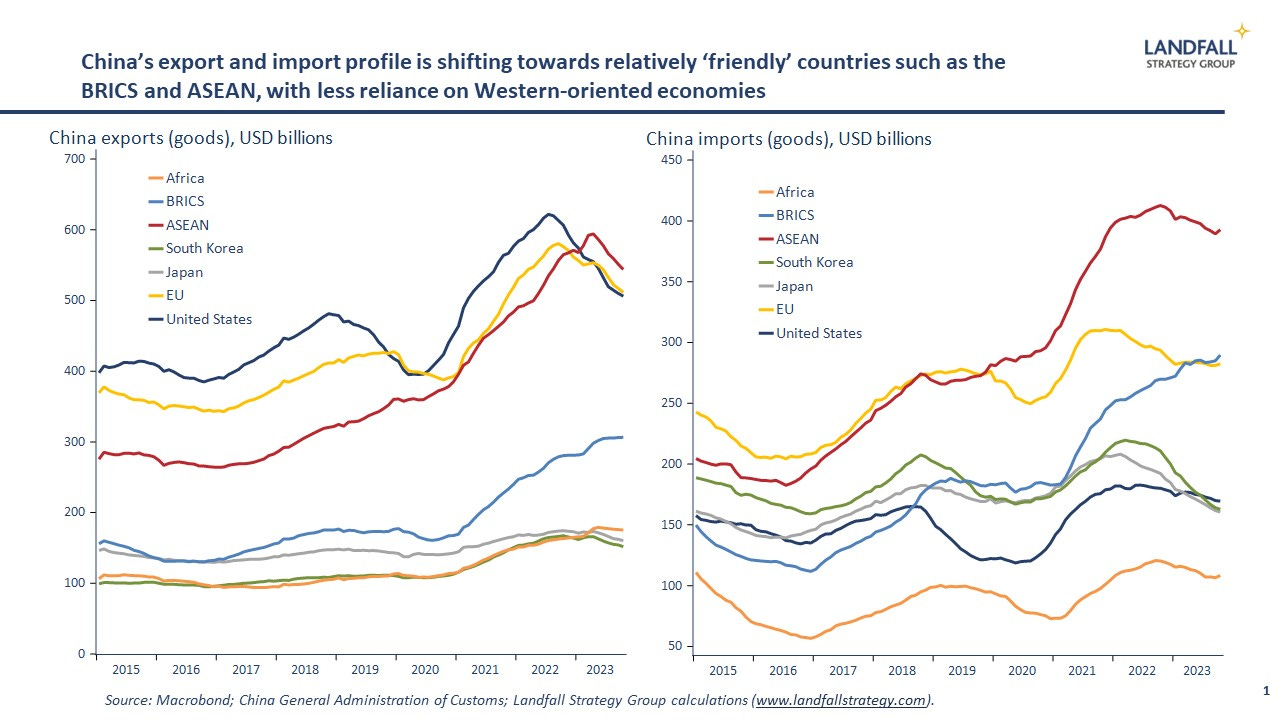

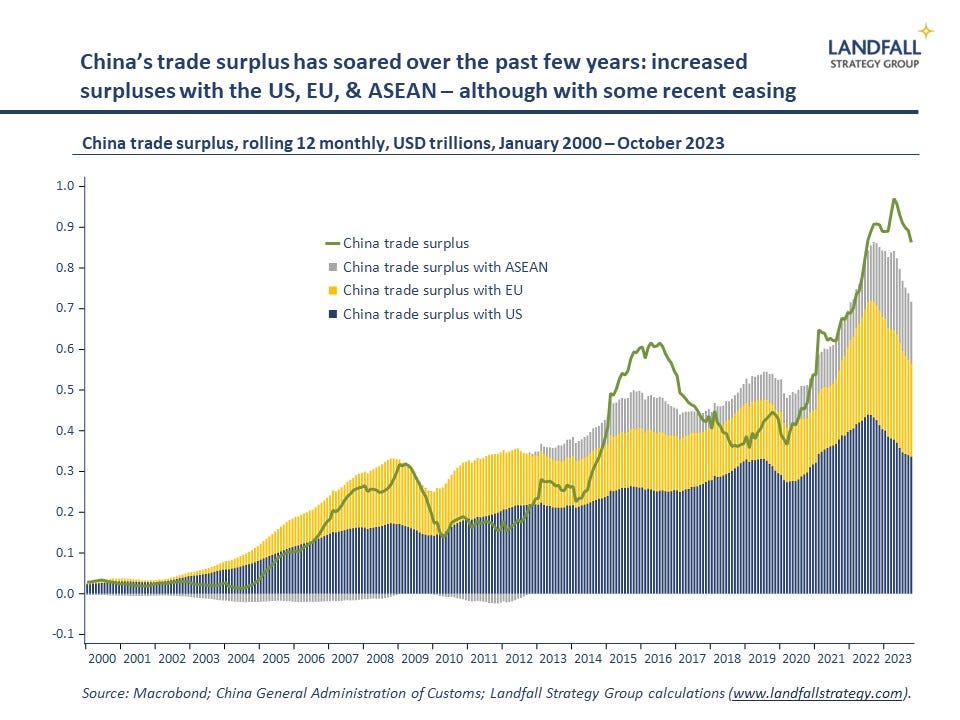

Last year we wrote that 2023 would be a year of ‘war by other means’, with multi-spectrum strategic competition between the big powers across trade, finance, technology, as well as military domains. And this is what we have seen over the past year: friend-shoring and economic de-risking activity is evident in the data, with trade, investment, and technology flows being shaped by geopolitical alignment.

As we look into 2024, we think the year ahead will be characterised by increasingly sharp, visceral competition – distinct from the norms established over the past few decades. Multi-spectrum strategic competition between geopolitical rivals will intensify, and will be accompanied by: increasing economic competition between friends; political competition in a year of consequential elections; competition for dominance between monetary and fiscal policy; and growing competition between labour and capital as labour markets tighten.

Politics will continue to be at the centre of global developments in 2024, reinforced by economic tensions: sluggish growth, high debt levels and sticky rates, and cost of living pressures.

The world may be due a quiet year after a succession of crises and shocks: pandemics, wars, inflation, and so on. This is possible: geopolitical guardrails may be established; immaculate disinflation may occur; the political centre may hold; and productivity growth may strengthen. But the strategic dynamics at work make a quiet year (unfortunately) unlikely.

1. Pick a side

Through 2023, friend-shoring and de-risking has become increasingly evident in trade and investment flows – a regular theme in these notes. And politics create an expansionary logic to strategic competition. The ‘small yard, high fence’ approach of the Biden Administration, with tight restrictions only imposed on narrowly defined sensitive technologies, is unlikely to be sustainable. Domestic politics in key countries will push for escalation and retaliation.

For many in the West, hard choices will need to be made. The Dutch and Japanese governments were pressured to restrict semiconductor machinery exports to China; and pressure has been imposed on various countries to not use Huawei technology. For its part, China is pushing the use of its technology to countries, that will de facto lock them into its technology and regulatory ecosystems.

For countries in and around the Western grouping, and that have significant economic and other exposures to China (notably countries in Asia), choices will be forced on geopolitical alignment. Although other countries are looking to maintain relationship across blocs, from India to the Gulf states and African countries, national choices will sharpen.

These choices are not just for countries. Firms and investors will also need to make choices, either because of government measures or because of commercially driven de-risking. Many Western firms and investors have made choices to reduce or restructure their China footprint to manage risks over the past year – and we expect this to step up. Even in sectors/activities that are distant from the technology frontier, there will be pressure to make choices about the acceptable level of geopolitical risk.

Choices will be forced on governments, firms, and investors in 2024, and decision-makers need to position for this proactively. Firms and investors will find it hard to straddle a fragmenting global system. This is not deglobalisation – global trade and investment flows will remain resilient, but will be increasingly shaped by geopolitics.

2. Friendly fire

There is also growing rivalry within blocs as large powers increasingly pursue their national interests in an aggressive, competitive manner. Despite the claims of Mr Putin and Mr Xi, friendships between countries do have limits. Countries have permanent interests not permanent friends, as noted by 19th century British statesman Lord Palmerston.

Although the response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to a strongly coherent Western response, there are significant, growing differences between the US and the EU (and others, like Japan and South Korea). The protectionist elements of the Inflation Reduction Act, and other aspects of US industrial policy, set up direct economic competition between the US and Europe. Similar tensions are seen between the US and its Asian partners.

These differences are likely to intensify in 2024. The America First agenda commands bipartisan support, and an inward-looking focus will become even more pronounced in a big US election year. And if Mr Trump or a similarly-minded candidate wins, the US commitment to allies and friends will be further diminished. Friends of the US from Europe to Asia need to start positioning for a more adversarial US posture.

China’s exporting of production over-capacity, and the large trade surpluses it will increasingly run with other emerging markets, will create tensions across the global south. China’s trade surpluses with ASEAN and Mexico are at record levels, for example. The expanded BRICS grouping is not particularly coherent to start with, and will become more challenged with these economic pressures.

Although there are geopolitical reasons for globe-spanning alliances and networks, 2024 will see an increased focus on national interest. This will create challenges for smaller, open economies that benefit from ready access to large economies.

3. The great contest

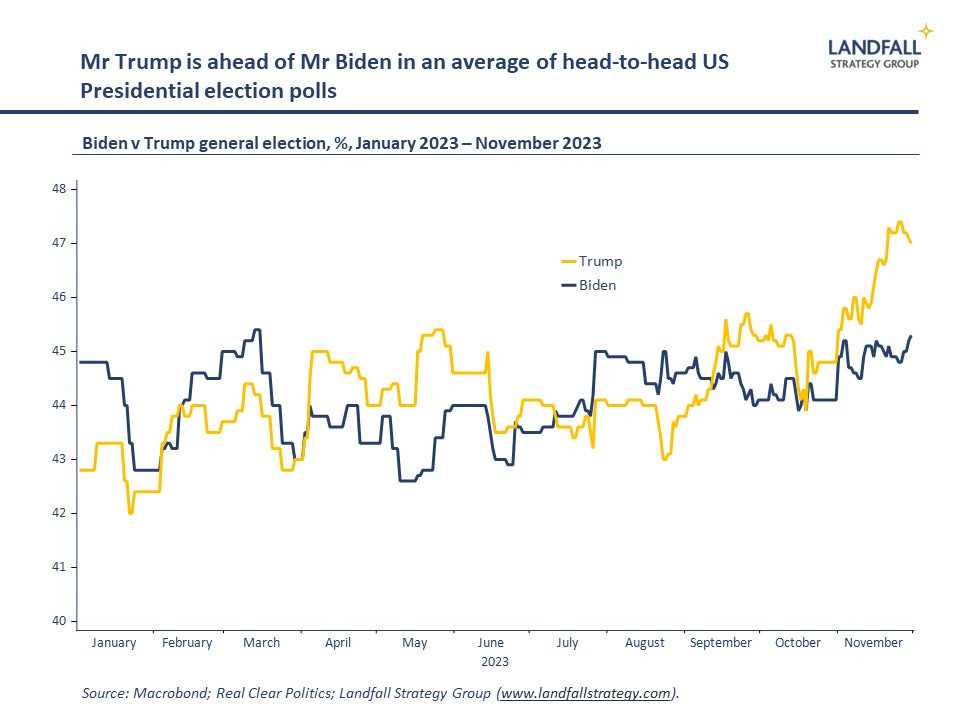

2024 is a year of consequential elections. Voters will go to the polls in countries accounting for >50% of the global population. Claims of the demise of democracy at the expense of autocrats are overstated, but 2024 will provide another test. And this series of elections has the potential to reset the global economic and geopolitical context.

The US Presidential election in November is obviously the key event. The risk is that not just that Donald Trump is re-elected but that American voters demonstrate disregard for the constitution, the rule of law and the reputation and role of the US abroad. This event would create a constitutional and political crisis (not least as Trump’s retribution committee becomes active) in the US, and would likely upset economic and investment activity, and likely alter the balance between the democratic and ‘non-democratic’ world.

As Europe shifts to the right, we expect the UK to move to the left in 2024 elections. This is now Labour’s to lose and despite the recent cabinet reshuffle, the credibility of the Tories is so badly damaged that we consider the outstanding issue to be the magnitude of a Labour victory.

Vladimir Putin will win the Russian vote, although turnout and the protest vote will be interesting to watch. In India, Narendra Modi is likely to stay in power next year. Finally, Taiwan’s election in January bears watching for its global implications – from the risk of war to global semiconductor supply chains. The incumbent DPP are currently favoured to win, something that would displease China. This election could influence the geopolitical tone for the year.

These elections in 2024 will have implications for markets and for economies. Expect more government spending as governments seek to strengthen economic activity – and the prospects of re-election. And there is the potential for ructions in markets if there are unexpected political results, notably in the US.

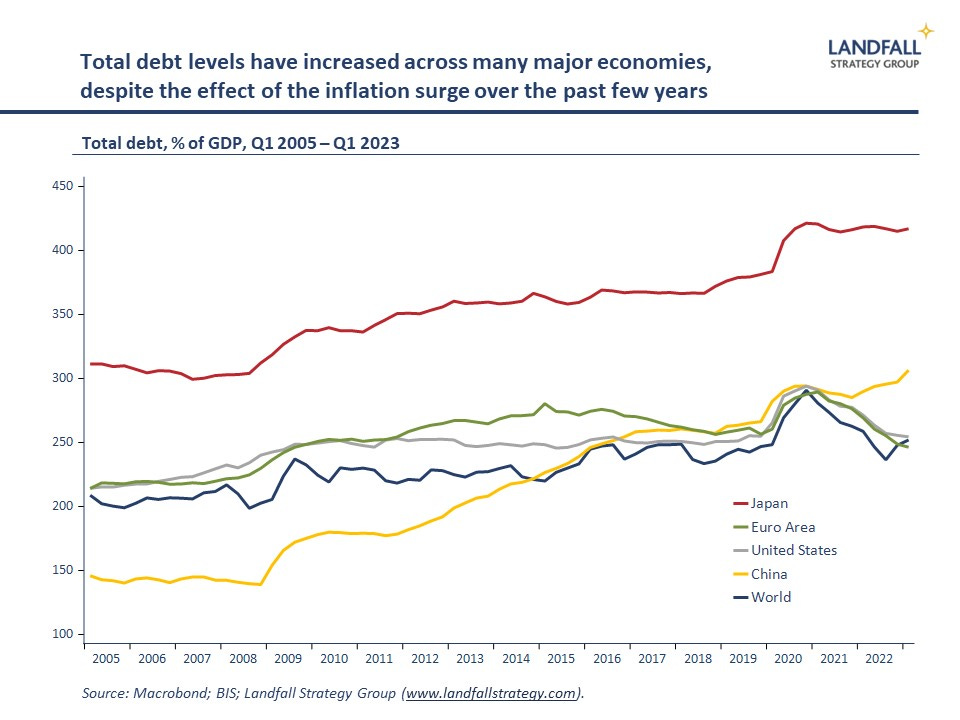

4. A world of debt

World debt to GDP is close to record high levels. In recent years this is something we associate with the eurozone but the new development is that debt levels in the UK and the US have pushed above 100% of GDP. The Japanese debt load remains heavy, and China’s debt has surged.

In that context, with interest rates remaining high, we enter 2024 facing an elevated risk of a debt crisis, or possibly a collection of regional debt crises. At least the fiscal burden of this debt load will heavily condition the fiscal debate – for instance the US now spends more on interest payments than it does on its military.

Should there be a debt crisis, we do not expect there to be a ‘committee to save the world’ as in previous crises because of the poor level of collaboration between the large economies (China and the US).

Looking ahead, while inflation is moderating the risk is that GDP growth slows and credit risk rises. So far, this is the ‘dog that has not barked’ in the sense that credit spreads have been well behaved, but our view is that spreads do not reflect the funding pressures that grow on countries and companies, and that in 2024 corporate leaders and policy makers will have to contend with less well behaved bond markets.

Expect increased tension or competition between monetary and fiscal policy institutions. We expect the austerity debate to return in some quarters; and in Europe at least we expect that ‘strategic autonomy’ projects in defence and green energy will increasingly be funded by infrastructure funds and new ‘green’ bonds.

Another possible policy response is bond yield suppression by central banks. The long period of quantitative easing created a backdrop in which debt accumulation became easy, but this policy option is hardly optimal and would lead to increased market volatility. But pressure will build on conventional approaches to monetary and fiscal policy as we move into 2024.

5. Marx’s revenge

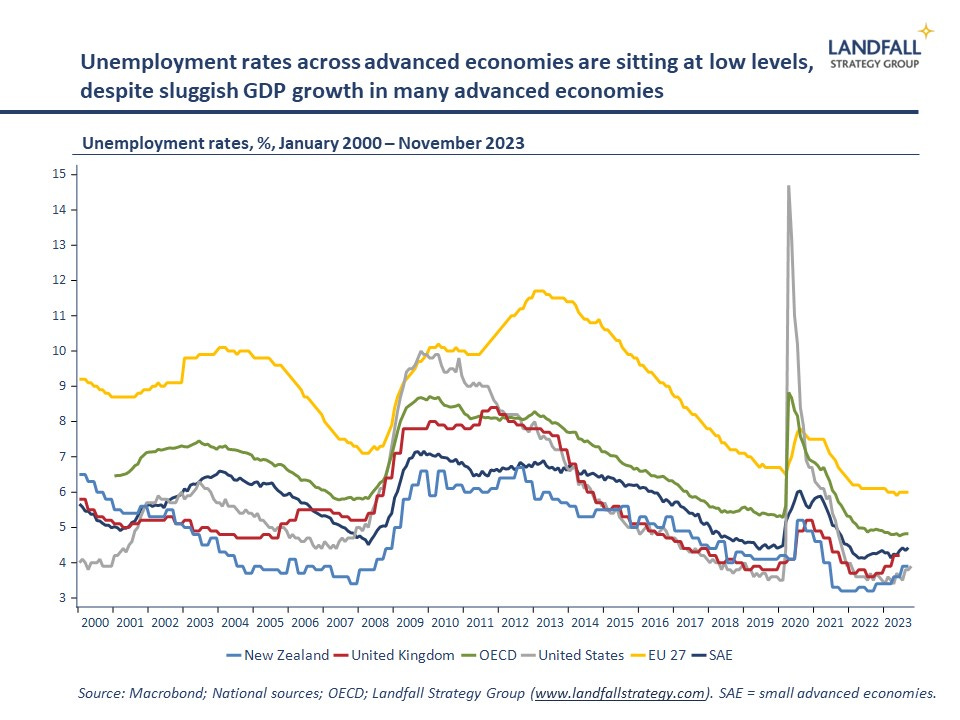

One of the striking characteristics of the pandemic recovery process has been labour market strength. These tight labour markets, with skills shortages across the economy, is changing the bargaining position of labour. Real wage growth is increasing and there is a step up in industrial action.

This tightness will persist. Populations are aging across the world, from Europe to Asia. This will constrain growth in the labour supply of many countries, as well as in the overall global labour supply. As the global economy normalises in 2024 after the pandemic shocks and disruptions, it will become evident that we are moving into a structurally different world of tight labour markets.

These ongoing tight labour markets will create a war for talent, with firms offering improved terms and conditions from higher wages to flexible working arrangements. These labour market pressures will support economic activity but will mean that higher inflation will be persistent.

On the other side, this higher rates, higher costs world will place pressure on firm margins. There will be growing tension between labour and capital as both compete for available returns. To use Marxian language, we anticipate growing competition between labour and owners of capital.

We also expect greater political friction around migration, even as labour market shortages emerge in many advanced economies. This is partly about cultural and cost of living issues (e.g. housing shortages), but also differences in interest between labour and capital. There is already ample evidence of political pushback on migration, from Europe to the US. Expect this to pick up further in 2024.

One way out of this conflict is improved productivity, which benefits both workers and firms. Investing in new technologies (automation, AI) as well as new business models is one response. And the response to geopolitical competition (such as industrial policy) may mean higher returns on capital and higher productivity.

At Landfall Strategy Group, we provide insights and advice to help our clients navigate economic and geopolitical risks and opportunities. Do get in touch if you would like to organise a briefing/presentation for your team, Board, or clients, or if you have a project that we can help with. Contact me by reply email or at david.skilling@landfallstrategy.com.

If you haven’t already, you can subscribe for free to receive my public notes - or take out a paid subscription to receive every note. Group & institutional subscriptions are available, with the option for regular 1:1 briefings.

If you liked this note, please hit the like button and also share it with your network:

Previous small world notes are available here:

You can also connect with me on LinkedIn.