The consequences of China’s growth model

China’s new (old) mercantilist growth model will lead to economic and geopolitical pressures around the world. War by other means.

Former New Zealand Prime Minister and UNDP head Helen Clark interviewed me recently on global economic and geopolitical developments. We had a wide-ranging conversation on issues from China and India to the Middle East and the US. The video is available here.

China is a central part of the global economic system (17% of global GDP, 14% of world merchandise exports); it would be difficult for China to be a status quo power even if it wanted to be. Even in previous, more geopolitically benign, periods, China’s rapid emergence into the global economic system led to widespread dislocation (as well as economic benefits): for example, the so-called ‘China shock’ on labour markets and specific geographies in the US.

Much of the recent attention on China’s economy has been its sluggish recovery from the pandemic. But more importantly, China’s emerging growth model will have significant spillovers into the global economy as well as political and geopolitical implications.

Under Mr Xi, China’s economic model combines mercantilism and industrialisation. There is no high-level support for a policy shift to a consumption driven growth model of the type long recommended to China; this is regarded as welfarism.

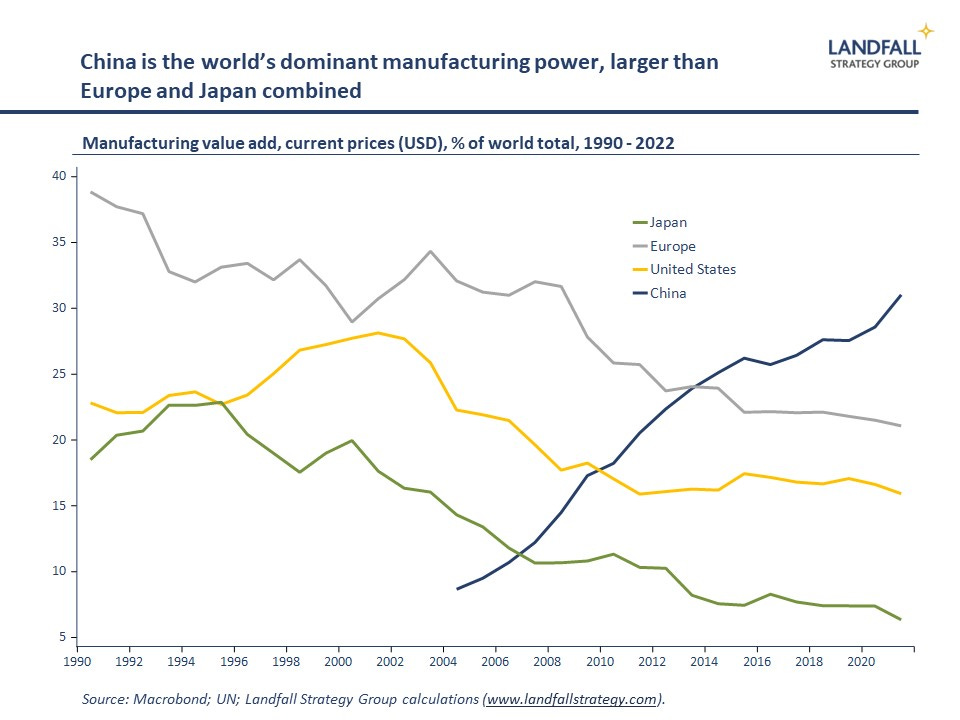

Rather, China wants to be an industrial superpower. It aims to dominate leading, sophisticated industrial categories while not giving up position in more basic industrial categories. And there will be increasing import substitution, partly motivated by concerns about exposure to trade/investment/technology restrictions. China generates ~30% of global manufacturing value added, and there are no indications that it wants to give that up.

Indeed, China is investing heavily in industrial production capacity. The President of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China recently observed that European firms could see ‘massive overcapacity’ in sectors such as auto, solar panels, wind turbines, chemicals, and metals. Or as the New York Times noted:

While the housing market struggles, factory construction fueled by government-backed financing is in high gear… China has already built enough solar panel factories to supply the entire world’s needs. It has built enough auto factories to make every car sold in China, Europe and the United States. And by the end of 2024, China will have built in just five years as many petrochemical factories as all of those now running in Europe plus Japan and South Korea. [New York Times, 6 November 2023]

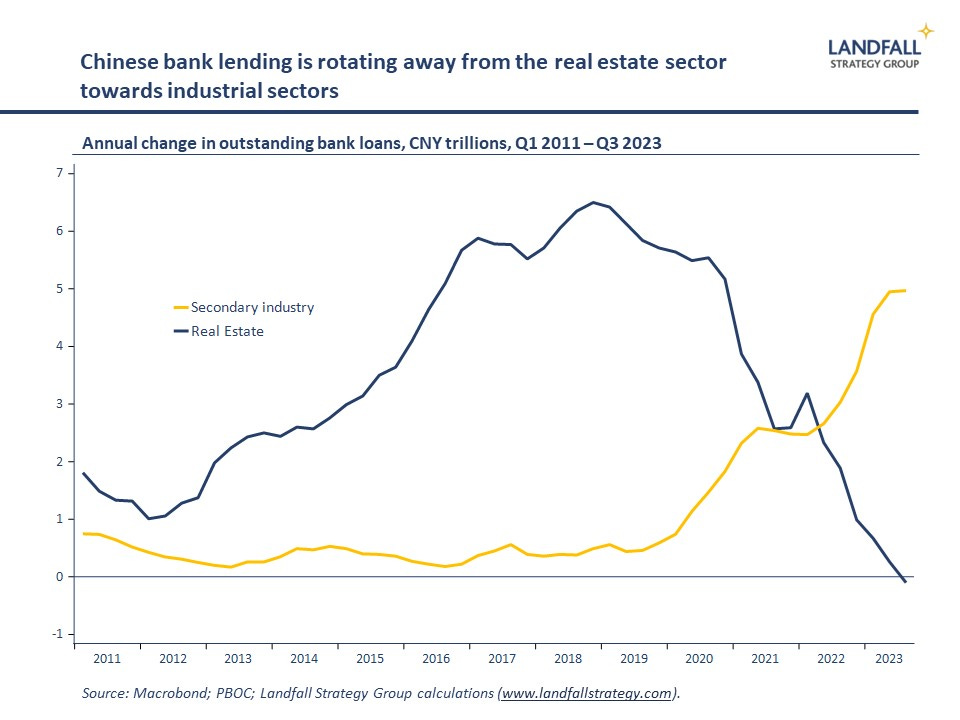

Banks are responding to this changed strategic policy direction. Outstanding loans to the real estate sector are contracting (-0.2% in the year to September) but bank lending is growing strongly in industrial sectors (+38% in the year to September).

Trade flows

China’s over-capacity relative to domestic demand means that much of this increased industrial production capacity will be export oriented. This is a replay of previous iterations of China’s growth model that caused widespread economic and political disruption, updated for new circumstances of geopolitical rivalry.

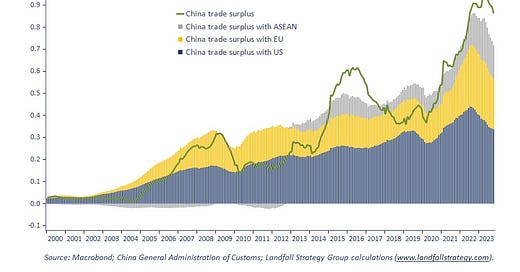

China is running a large trade surplus, even if it has eased over the past several months in the context of contracting world trade. This reflects resilience in China’s export performance. And there are some categories in which China is performing very well: China has become the world’s largest car exporter, capturing increased market share in Europe and elsewhere – with particular strength in electric vehicles. And China is winning market share in other sectors, from batteries to renewables.

Similarly, China’s industrial strengths are supporting an import substitution agenda as it seeks to reduce exposure to geopolitical rivals. It is making progress in semiconductors; note Huawei’s recent phone with surprisingly advanced chips. This is partly supported by intensive stockpiling of Western technology in advance of sanctions, but also reflects strengthening domestic capabilities.

These are often highly sophisticated products. For a middle income country, China ranks highly on measures such as the global innovation index. But state subsidies and other support also allow Chinese firms to gain market share by selling these products cheaply. And the CNY/USD is at a 15-year low, which also supports Chinese competitiveness.

However, there are meaningful economic and political constraints to this economic model. Western economies will not accept sustained, large trade deficits with China: trade surpluses with the US and EU account for about two thirds of China’s overall trade surplus. The EU has been complaining loudly about unbalanced trade, and has launched anti-subsidy investigations into electric vehicles. Similarly, the trade deficit with China is a neuralgic issue in the US – particularly among America First Republicans like Mr Trump. Expect further measures to try to reduce this deficit.

Advanced economies will not allow for a replay of the last wave of Chinese market share gains and economic dislocation – and particularly in categories that are seen as strategic, such as electric vehicles, batteries, solar panels, and wind turbines. These sectors are central to many Western economies, such as auto in Germany and renewables in Denmark. Indeed, there are particular exposures for small advanced economies given their concentrated export structures.

The economic impact of China’s growth model on advanced economies means that it will be politically contested. It will be hard for China to expand its trade surplus and to win further market share in advanced economies because of domestic political dynamics. This is reinforced by the geopolitical environment in which Western economies are already looking to de-risk from China and to build increased strategic autonomy. Expect growing political pushback on China’s external balance and export-oriented growth model, with more trade and investment restrictions.

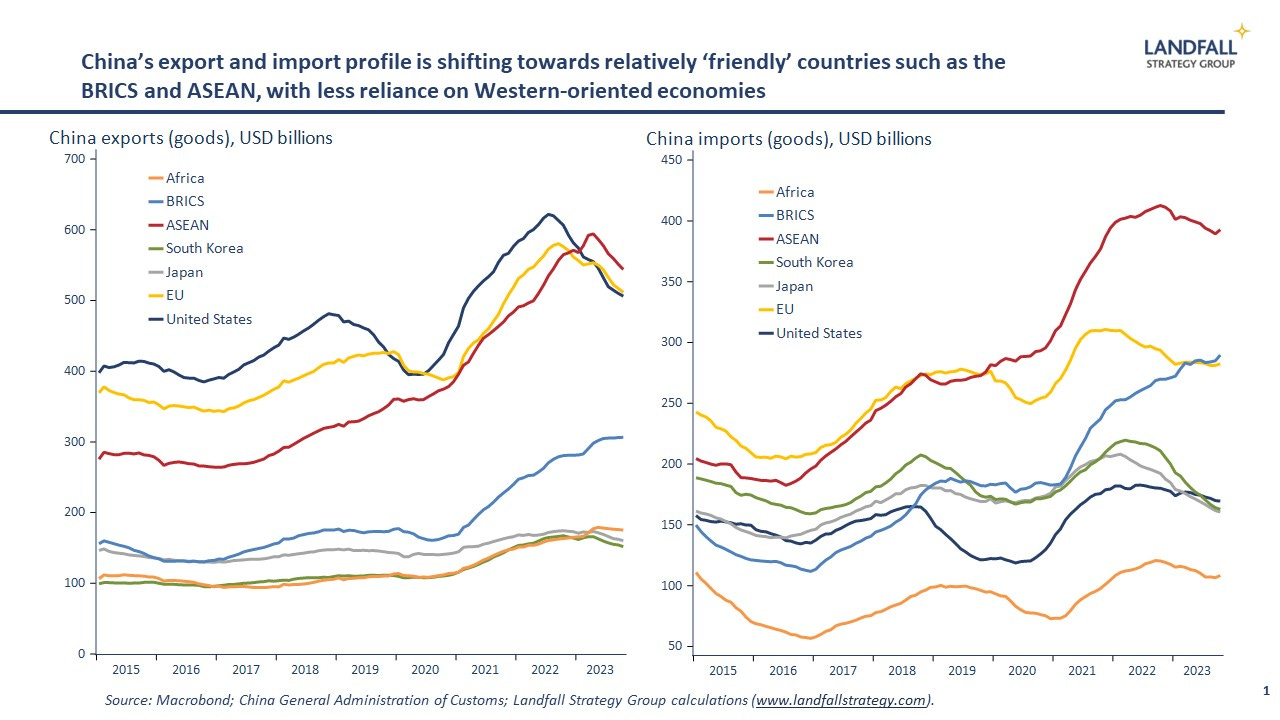

If Western market access is constrained, China’s excess production capacity will need to be vented elsewhere. One obvious group of countries are emerging markets. There is an increasing tendency towards friend-shoring in China’s trade profile, with China’s exports and imports rotating towards ASEAN, the BRICs, Africa, and so on.

This is one way of thinking about initiatives like the BRI and the expanded BRICS grouping. China will be looking to further strengthen its position itself as dominant suppliers to these markets, offering cheap, good quality goods and services (and often with financing). The growing exports to these economies will likely continue. Indeed, trade surpluses are emerging with non-Western economies such as ASEAN.

This will have implications for the growth models of emerging markets. Chinese competition in terms of exported manufactures will make it difficult for these countries to develop a manufacturing base (unless they can seize opportunities from friend/near-shoring activity).

Capital flows

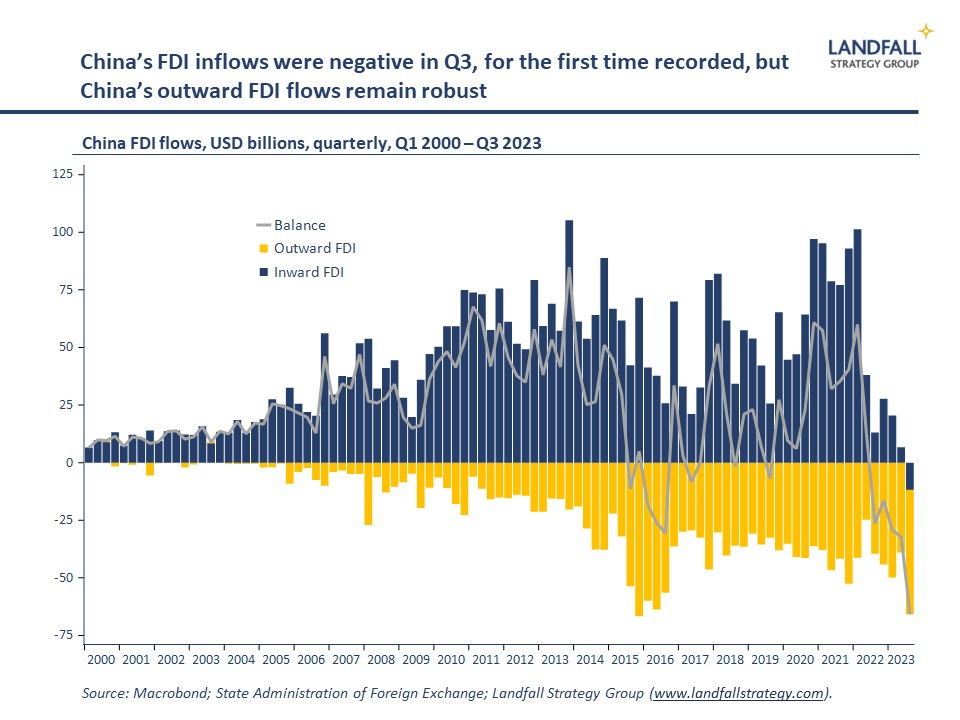

Capital flows in and out of China also provides an interesting lens on this growth model. China’s inward FDI was negative in Q3 for the first time in recorded history: foreign firms are staying away from China, and are withdrawing capital from China. These reduced FDI inflows are partly because of the heightened geopolitical risks, as well as firm concerns about the domestic business/political environment in China.

So the externally-oriented activity is increasingly driven by Chinese firms: ~60% of Chinese exports are by private sector Chinese firms, suggesting rising Chinese competitiveness. The export share from foreign invested firms in China is now 30%, down from a 55% share in 2010.

However, outward investment flows from China have been holding up, with significant Chinese greenfields investment around the world. In Hungary, for example, substantial investments are being made in EV battery plants by private sector Chinese firms like CATL. There are also substantial Chinese FDI flows into South East Asia. And China’s sizable current account surpluses provide ample funding for this investment.

So expect increased Chinese physical presence in many markets – in some cases to get around trade and investment restrictions imposed on activity in China (see my recent reference to ‘Singapore-washing’ by Chinese firms).

Overall, China’s growth model remains outwardly-focused based on heavy investments in a range of industrial strengths. The consequent trade surpluses and competitive pressures are likely to cause political/geopolitical tension and to be contested across many advanced economies. Despite the warm words from Presidents Xi and Biden in San Francisco during the week, this is war by other means as economics and geopolitics intersect.

At Landfall Strategy Group, we provide insights and advice to help our clients navigate complex economic and geopolitical risks and opportunities. Do get in touch if you would like to organise a briefing/presentation for your team, Board, or clients, or if you have a project that we can help with.

If you haven’t already, you can subscribe for free to receive my public notes - or take out a paid subscription to receive every note. Group & institutional subscriptions are available, with the option for regular 1:1 briefings.

If you liked this note, please hit the like button and also share it with your network:

Previous small world notes are available here:

You can also connect with me on LinkedIn.