Political regime change

Beyond the busy election calendar, structural changes in politics and policy are underway across advanced economies – with material economic consequences

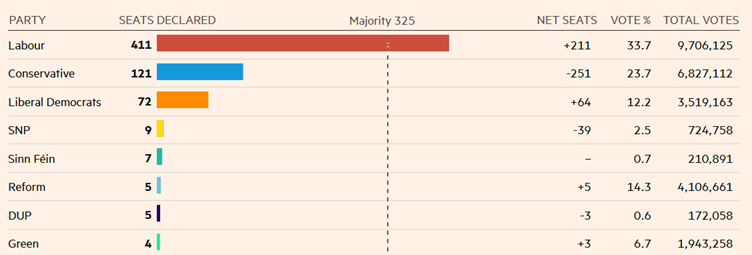

It has been a busy week or so in politics around the world. Last Thursday’s UK election delivered a landslide victory for the Labour Party (411 seats v 121 for the Conservatives), supported by widespread tactical voting: Labour’s vote share was 34% v 24% for the Tories.

This provides a stable basis for governing, and the new government has started well in terms of policy announcements, Ministerial appointments, as well as tone. This is important because the UK faces deep challenges; the UK has been the weakest economic performer across the G7 since Covid.

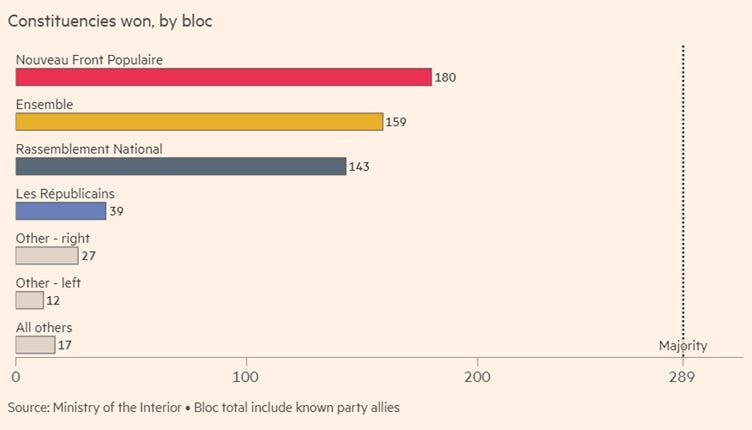

This political stability contrasts with France. Last Sunday’s second round of voting in the legislative elections delivered a surprise result, with the left wing grouping (Nouveau Front Populaire) taking first place (although not a majority), followed by Mr Macron’s Ensemble, with Ms Le Pen’s Rassemblement National in third place (having threatened to place first). This was the result of the left wing grouping coming together, and many candidates dropping out to avoid splitting the vote against the RN.

This is uncharted territory for France. There are multiple possible scenarios for assembling a new government, but none of these will be straightforward. Some coalition between parties in the centre and on the left is plausible (excluding Mr Melenchon’s far-left party). Even so, significant political instability is likely with difficulty in pursuing a coherent policy agenda. The reforming agenda of Mr Macron is over. Mr Macron’s gamble of snap elections has strengthened the extremes, weakened the centre, and raised political risk: it has not been the ‘clarifying event’ he promised, although it is clear that there is a substantial anti-RN vote.

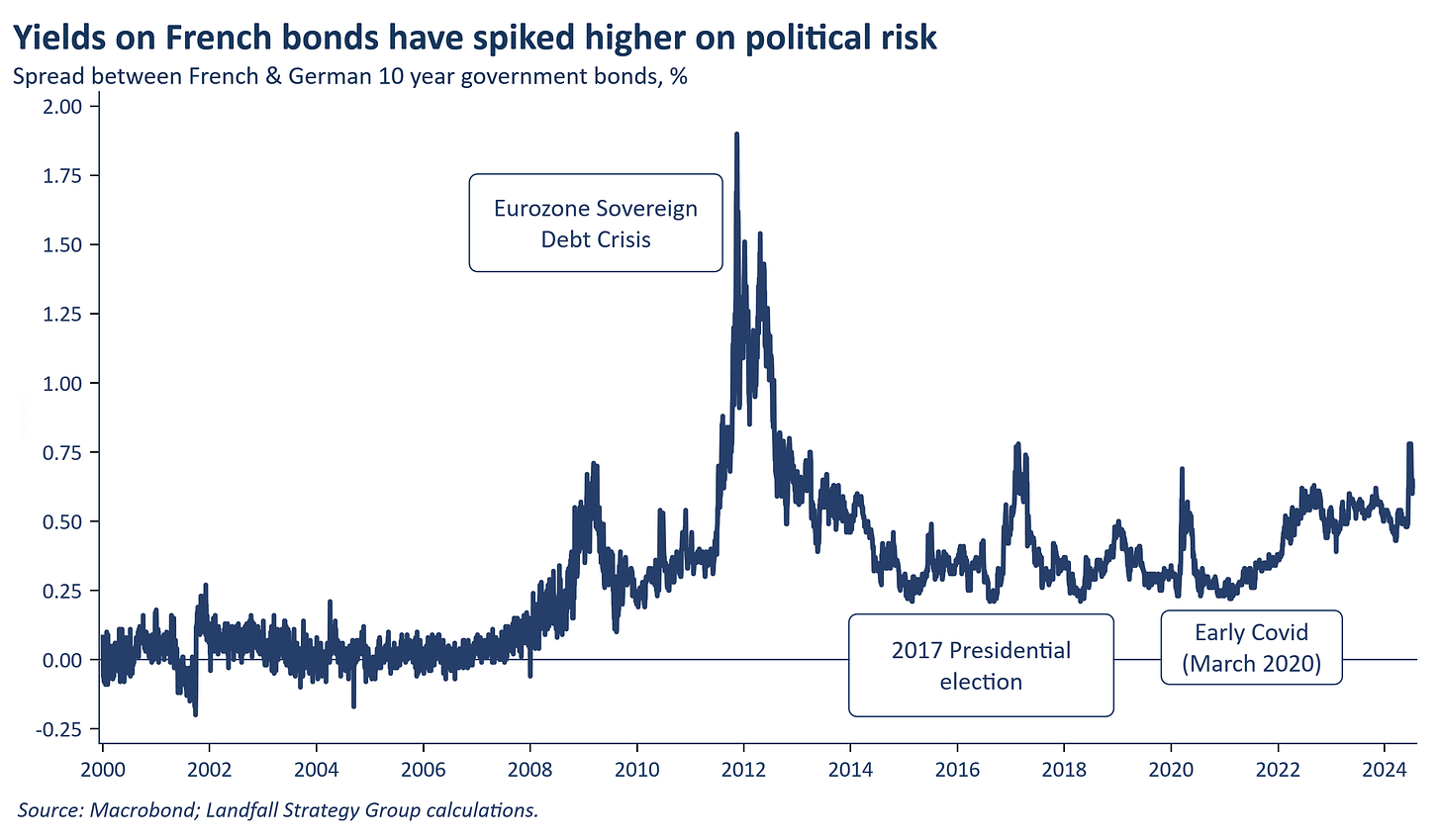

Among other things, this political instability will make it difficult for France to address its fiscal issues; the EU has already started an Excessive Deficit Procedure against France. A collision between France and EU institutions is increasingly likely: ‘le spread’, the gap between French and German government bond yields, is a useful risk proxy. More broadly, French political uncertainty combined with a weak German government will compromise the ability of the EU to work coherently.

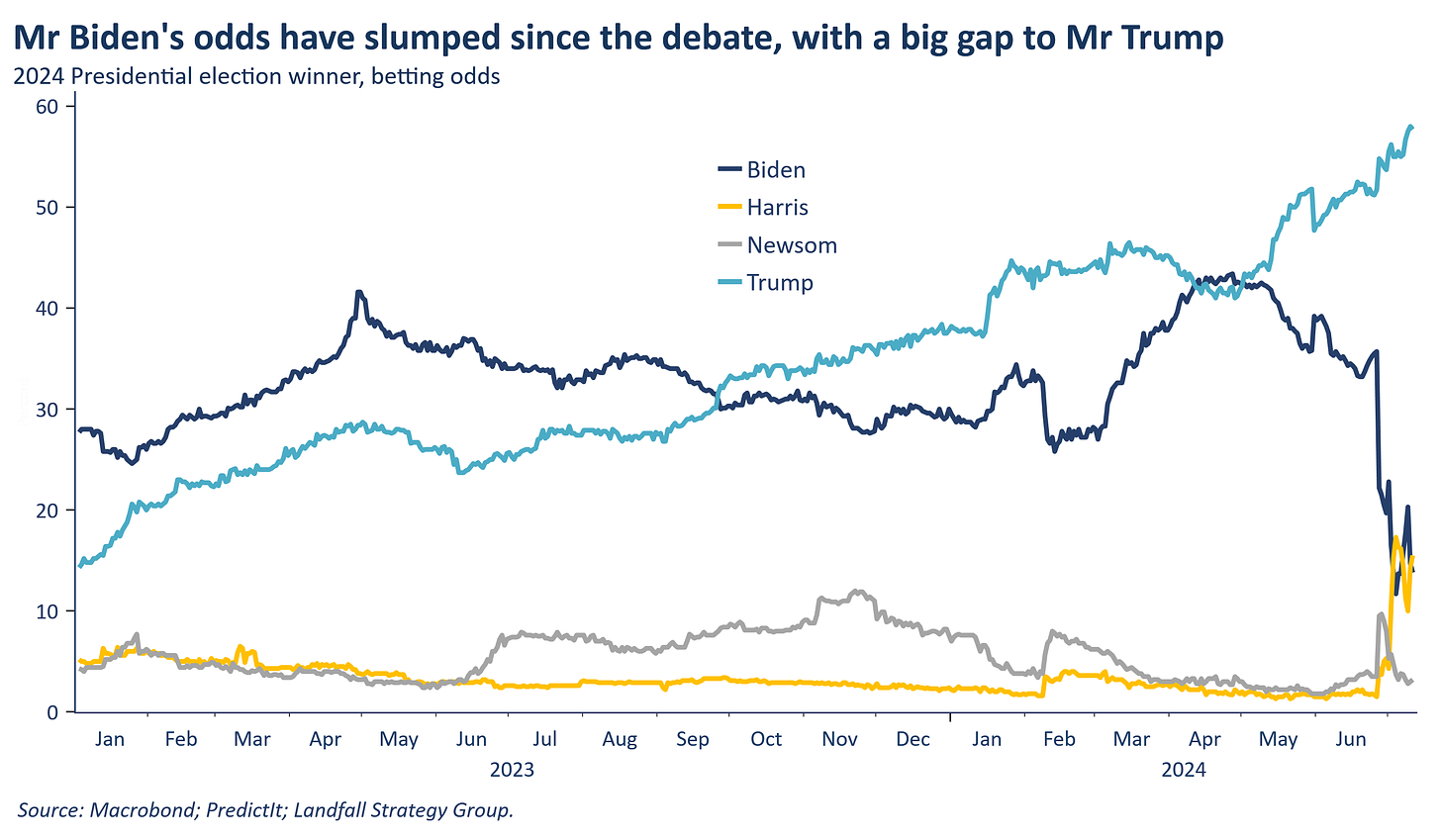

And in the US, there is heightened uncertainty about whether President Biden will contest November’s election on concerns about his age and mental capability. He is aggressively committing to stay in the race, and it is not straightforward to remove Mr Biden involuntarily as the nominee. But prediction markets have priced a meaningful chance that a nominee other than Mr Biden will contest the Presidential election – with VP Kamala Harris currently priced as the most likely.

This decision, and its impact on the Presidential election, will be deeply consequential for the US and the global economic and political system.

For more detailed analysis on these elections, and to discuss the implications, do get in touch: david.skilling@landfallstrategy.com

Regime change

Each of these events responds to country-specific factors: voting out the Conservatives after 14 years; frustration/anger at Mr Macron; and the peculiar state of US politics. But these events also reflect structural political changes, which have the potential to lead to material changes in policy settings and economic outlooks.

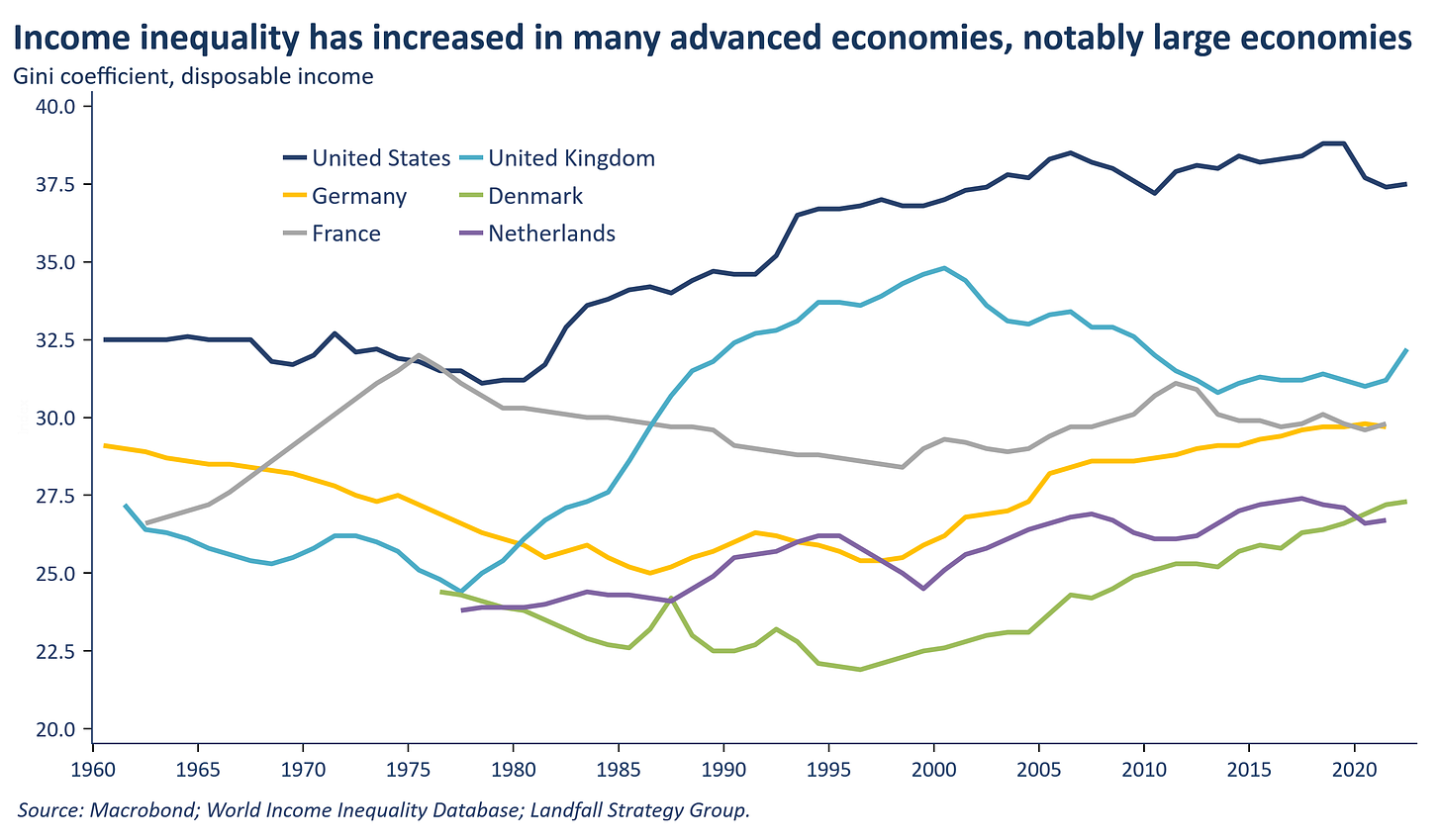

Very broadly speaking, the policy consensus across advanced economies over the two decades prior to the global financial crisis was for fiscal discipline, openness and international engagement, and flexible markets. This supported economic performance, but the risks and downsides of this policy approach were not always managed well: leading to instances of underinvestment, inequality, risks transferred to households, low real wage growth, high debt, and so on.

Political fractures began to emerge after the global financial crisis, but there was a limited policy response. This led to the political earthquakes in 2016; the Trump and Brexit votes represented pushback against consensus policy positions – with a sense that policy elites had not delivered.

Although Mr Trump lost in 2020 and Brexit is now widely regretted, these underlying pressures remain: Mr Trump is ahead in the polls, and right-wing populist parties have made gains in European Parliamentary elections as well as in national elections in France, the Netherlands, and elsewhere. And post-Covid inflation pressures have corroded trust in institutions, strengthening political extremes.

The political centre of gravity is shifting. This is not a left v right distinction – these terms make less sense than they used to. But there is a shift towards less open policy settings. On trade, there is increasing protectionism and little appetite for trade agreements; and there is widespread pushback on migration.

There are also pressures for more government spending on public services, infrastructure, housing, insurance against shocks, and so on. Even nominally right wing parties are reluctant to cut government spending. This is reinforced by the pressures of geopolitical rivalry, from military spending to industrial policy.

In areas from macro policy to trade and the environment, there is a desire for policy discretion rather than rules. Voters in many countries are responding to political parties that criticise domestic policy rules and constraints, as well as international rules from the WTO to EU emissions and migration rules.

In the near-term, the impact on economic performance is unclear. A bigger fiscal impulse, for example, could be good for GDP growth (albeit inflationary). And increased government investment in innovation is likely a good thing. But over time these political dynamics are likely to lead to less dynamic economies with weaker outcomes.

These political dynamics will intersect with structural economic and geopolitical changes, to meaningfully shape economic and market outcomes. Over the past several years, policy settings have been knocked off the domestic political and geopolitical equilibrium that held from the early 1990s – and a new policy equilibrium will need to be found. There will be a lengthy, bumpy process of political realignment, as political parties and systems respond: for example, today’s US Republicans and UK Conservatives look very different than they did in the 1980/90s.

Institutional risk

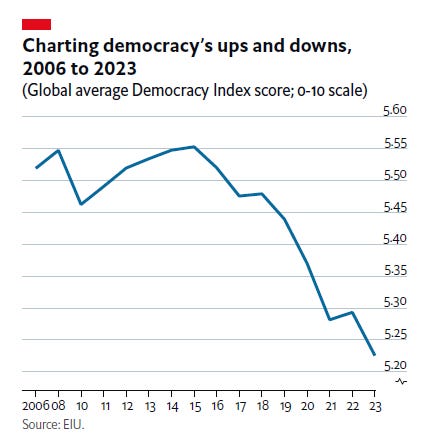

Beyond these policy pressures, there are deeper political and institutional risks. Across advanced economies, trust in political institutions is low, there is weakening support for democratic governance, as well as growing political polarisation. The US is a clear example of this.

Measures of democratic strength have been retreating for some time (what some call ‘a democratic recession’). This should not be overstated: recent election results (India, France, Turkey) suggest that there is resistance to authoritarian tendencies; and voters punish incompetence (as in the UK).

But it is also clear that there is widespread dissatisfaction with many governments and political systems, and growing demand is reported for ‘strong leadership’ to fix problems. There is heightened potential for significant political disruption in advanced economies (and beyond) over the coming years.

This should not be surprising. History is punctuated by periods of political disruption – particularly during/after periods of economic change – as recent books by Fareed Zakaria and others remind. My summer reading includes a book about political revolutions in 1848-49, a period of political turbulence that spread across Europe – with some parallels to the current context.

So as well as strategic competition between countries, there is also competition between different models of governance within countries. In the near term, I am more concerned about domestic political and institutional risk in major economies than about geopolitical rivalry, which I think can be managed tolerably well.

These structural political dynamics should be taken seriously in assessing economic and policy outlooks, and in pricing assets and allocating capital.

If you find these notes valuable, do consider subscribing to receive our in-depth insights and advice. We provide regular briefings to firms, investors, and governments on critical issues at the intersection of global economic and geopolitical dynamics; deliver presentations on global macro, geopolitical, and policy developments; and also prepare commissioned analysis.

You can contact me at david.skilling@landfallstrategy.com to schedule an introductory call. We would be pleased to share some perspectives on global economic and geopolitical issues and discuss how our services can benefit you.

Related insights:

Election risk ahead, 14 June 2024

Geopolitics & macro policy, 9 February 2024

Positioning for Trump, 12 January 2024

To receive my notes on global economic & geopolitical issues, please do subscribe.

If you liked this note, do forward it - or share it with your network:

Previous small world notes are available here:

You can also connect with me on LinkedIn.