Capital wars

Alongside high profile trade wars, expect structural change to cross-border capital flows - which will be at least as disruptive to the global economy

After the shock of Liberation Day, markets have recovered their losses as Mr Trump has paused these high tariffs and struck holding deals with China and the UK. But this market relief is overdone. The structural rewiring of the global economy is only just getting started and ongoing economic and market turbulence is likely (as we saw on Friday), due to Trump Administration policy, the actions and responses of others, as well as structural economic and geopolitical dynamics.

As one example, efforts to rebalance global trade flows will contribute to structural change in global capital flows: current account deficits are the mirror image of capital/financial account surpluses, and vice versa. New patterns of global trade will lead to changed cross-border capital flows, as well as to growing competition for capital, increased capital nationalism, and over time perhaps to financial repression. Trade wars are a precursor to capital wars. Indeed, a fragmented global economy in terms of capital flows is likely to emerge more sharply than in terms of trade flows.

Changing global capital flows will have implications for the location of productive investment and economic growth, the financing of government borrowing, as well as exchange rates and asset prices. This note selects seven charts that provide insights on global capital flows and related developments.

Do get in touch if you would like to discuss the implications of global economic and geopolitical dynamics for your strategic positioning and capital allocation. In this new world, macro dominates micro.

1. Global imbalances

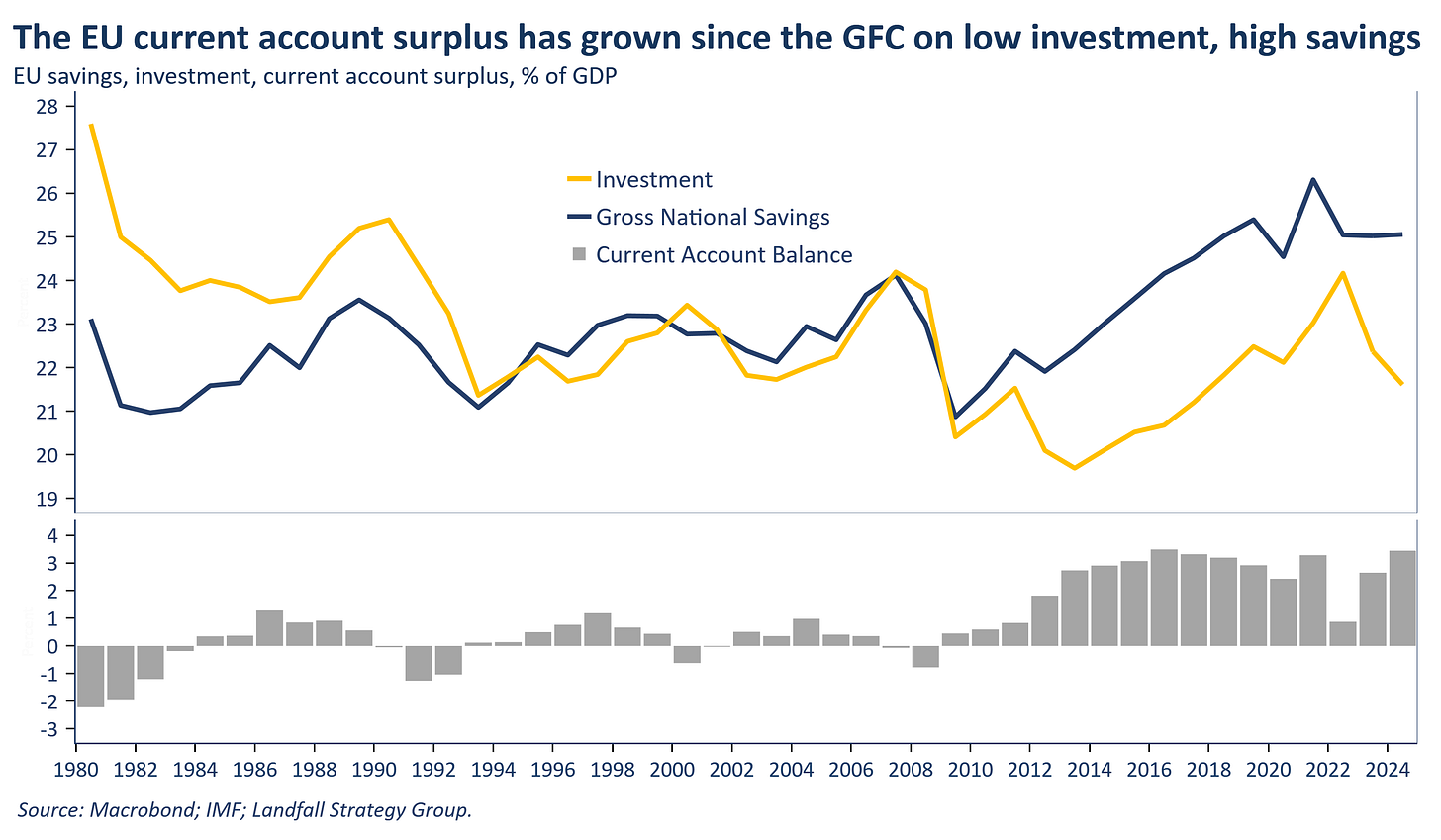

Aggregate current account deficits/surpluses are below their peak prior to the global financial crisis, but remain sizable: G7 finance officials noted ‘excessive imbalances’ last week. The US is the largest deficit country, and Japan, China, and the EU have large surpluses. The US has received substantial capital inflows from these current account surpluses countries, helping to finance its budget deficit and bidding up US asset prices. But the EU’s current account surplus will likely reduce on increased government spending (notably in Germany), as will surpluses across East Asia as export-oriented growth models are adjusted. There is also a structural shift in Middle East current account positions, on increased government spending and investment. Together, there will be less foreign capital available to the US (despite the eye-wateringly large investment commitments into the US that President Trump has announced). This global rebalancing is likely to be a disruptive process.

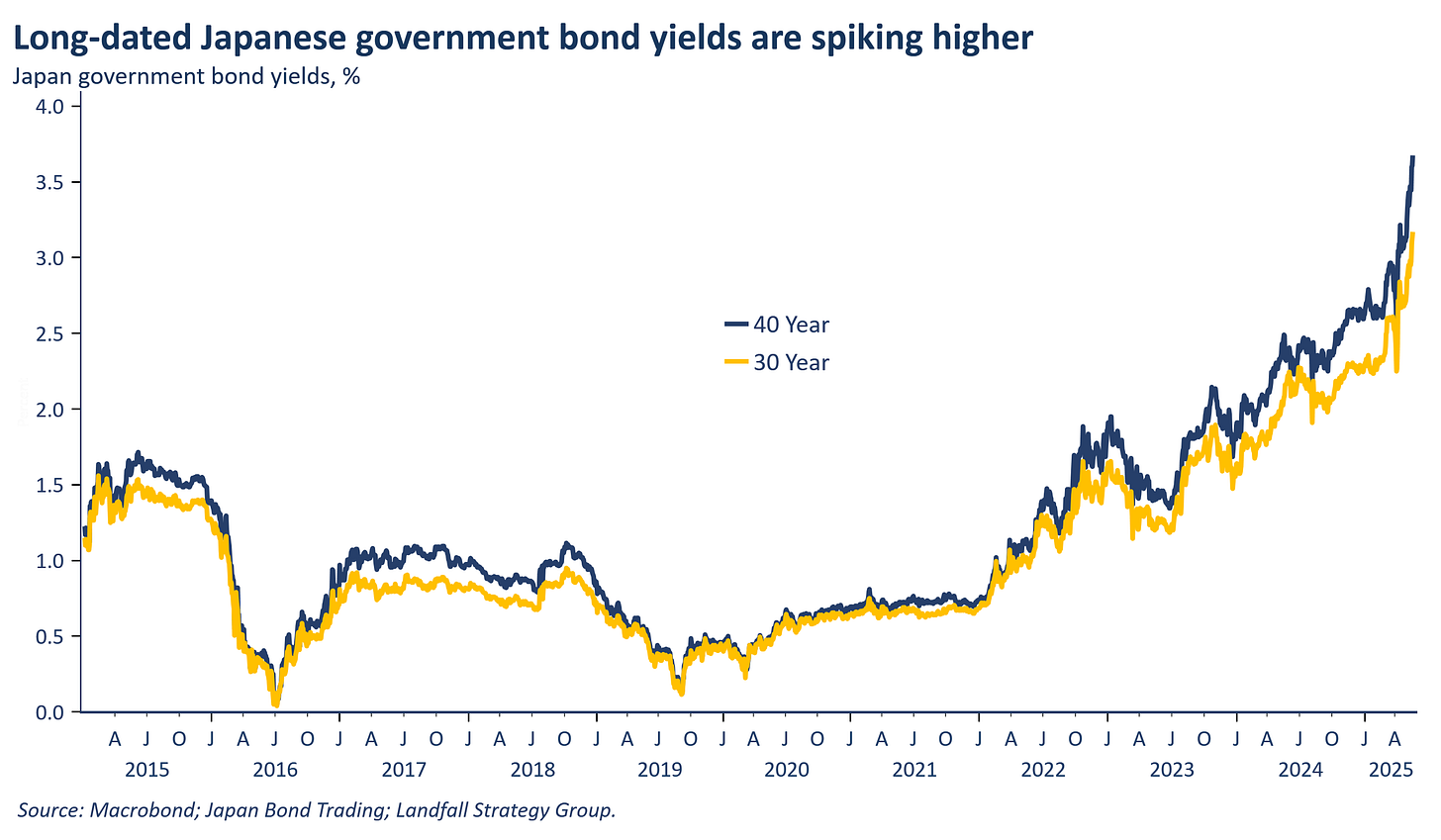

2. Japanese earthquake

Japan is one of the largest international investors in the world, with a net international investment position of ~$3.5 trillion (~3% of world GDP): the decisions of Japanese investors can shake the world. One thing to watch closely is the repatriation of Japanese capital: yields on Japanese 30-year government bonds spiked to >3% last week, partly on the back of difficulties in selling government securities. If capital is repatriated to Japan due to higher interest rates and an expected stronger JPY, significant demand may be removed for US Treasuries (Japan owns ~$1.1 trillion, and is the largest single foreign holder) as well as for US equities. The ‘normalisation’ of Japanese macro policy is likely to be deeply consequential for the global economy.

3. Europe invests

The EU has relatively high private and public sector savings, but relatively low investment. Its current account deficit (~3.5% of GDP) reflects the export of this net savings, including to the US. But expect reduced government savings, particularly in Germany, to finance investment in defence, infrastructure, energy, and more. The EU’s current account surplus will contract on increased government investment – and European capital will be brought home to finance this investment. This capital repatriation is happening organically at the moment, as some European institutional investors derisk from the US. But over time, expect that political pressure will build on government-funded investment vehicles or pension funds to invest more at home (Mr Macron is already indicating initiatives in this direction).

4. Constrained Chinese outflows

China’s current account surplus has increased to ~3% of GDP in the year to Q1, due mainly to a record trade surplus in goods. However, this current account surplus is likely to gradually reduce as China shifts to a less mercantilist economic model over time, in response to both domestic and international pressures. This implies reduced net capital outflows from China (as a share of GDP), whether into US Treasuries or to finance infrastructure initiatives through the BRI. In addition, the markedly lower inward foreign portfolio and direct investment into China over the past few years – due to both economic and geopolitical risks - will likely be sustained, further constraining the space for outbound Chinese investment. Chinese capital outflows will become increasingly selective behind strategic priority areas; US assets are not likely to be at the top of the list.

5. US Treasury ownership

One of the big stories of the past several weeks has been the potential for US derisking by international investors. Although there is no persuasive evidence of a material sell-off in foreign holdings of US Treasuries since Liberation Day, there has been an ongoing reduction in the foreign ownership share of US Treasuries over the past decade, including by foreign official investors such as central banks. Foreign investors now hold ~30% of Treasuries down from ~50% in 2013. To the extent that current account surpluses reduce in Europe and Asia, key sources of foreign demand for US Treasuries are likely to continue to soften. This is a problem given the rapidly growing US government financing requirement, and will contribute to higher borrowing costs.

6. Bond vigilantes

The US federal budget that is now working its way through Congress is assessed to increase the fiscal deficit, largely on various tax cuts. US public debt will increase to an estimated 125% of GDP within the decade, uncharted territory in peacetime. This ‘big beautiful bill’ is getting negative reviews from investors, with longer-dated bond yields moving up sharply. This is a self-perpetuating problem: one of the key drivers of an expanding fiscal deficit is higher debt servicing costs. But absent intrinsic fiscal discipline among politicians, bond vigilantes may provide the constraint - forcing a fiscal adjustment (eventually). Or quite possibly leading the government to resort to unorthodox financing measures, including through the Fed.

7. US twin deficits

The US current account deficit has been widening over the past several years on a weaker goods export balance as well as lower investment income. Another way to look at this is through sectoral savings: the current account balance is arithmetically the same as net national savings. The US current account is driven largely by the high fiscal deficit (~7% of GDP). Fiscal policy choices are much more consequential for the US current account deficit than are tariffs: there is a direct tension between efforts to reduce the US trade deficit and the current expansionary US fiscal policy. But over time, higher bond yields may increase private and public sector savings, leading to a smaller US current account deficit. And in the extreme, financial repression measures to require higher private sector savings are also possible.

Do get in touch if you would like to arrange a discussion of the implications of these issues: I’m at david.skilling@landfallstrategy.com or on LinkedIn.

To receive my free public notes on global economics & geopolitics, subscribe here:

If you liked this note, do forward it - or share it with your network: