The rise and rise of public debt

Public debt continues to rise across advanced economies, creating economic and geopolitical risk exposures

I began writing this note in Paris (in town to talk to global dairy executives about global economic and geopolitical dynamics). But beyond the autumnal beauty of Paris, economic and political stress and uncertainty is evident.

A messy domestic political context (since the snap legislative elections in July) is worsening fiscal challenges. The French budget deficit is ~6% of GDP, well in excess of the EU’s 3% target (France is already under the EU’s excessive deficit procedure). The recent French budget proposed by new PM Barnier pushed the deadline for meeting this target out to 2029, relying on a large number of temporary revenue raising measures. Markets are unimpressed: the bond spread between French and German 10 year government bonds recently touched 80bp, a multi-year high.

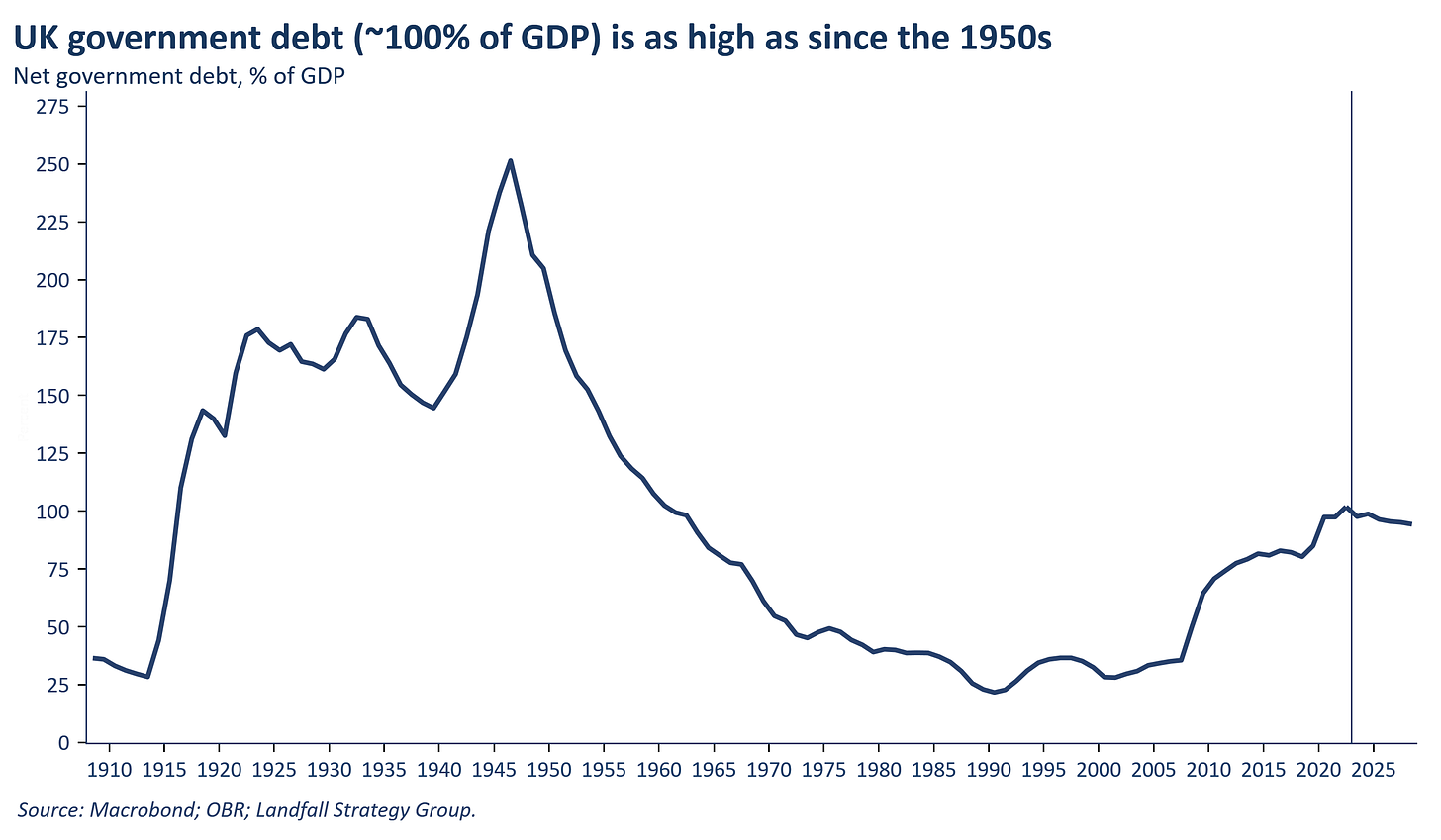

Of course, France is not the only country facing fiscal challenges. The new UK government are delivering their first budget on October 30, juggling a high and growing debt profile with the need to finance investment to generate stronger growth. Fiscal rules are likely to be adjusted to allow for debt-financed productive investment; and various taxes will be raised. But memories of the Truss shock linger, and the government feels pressure to demonstrate fiscal discipline.

A combination of domestic political realities (the rise of populism, the absence of a political constituency in favour of fiscal discipline) as well as economic pressures (higher debt servicing costs, aging populations) make it difficult to see how meaningful fiscal consolidation is likely – and particularly in what is a low growth environment in many advanced economies. And new demands on government balance sheets are growing: military spending, infrastructure, industrial policy, and more. The most likely way is up for public debt, even though it is already at peacetime records.

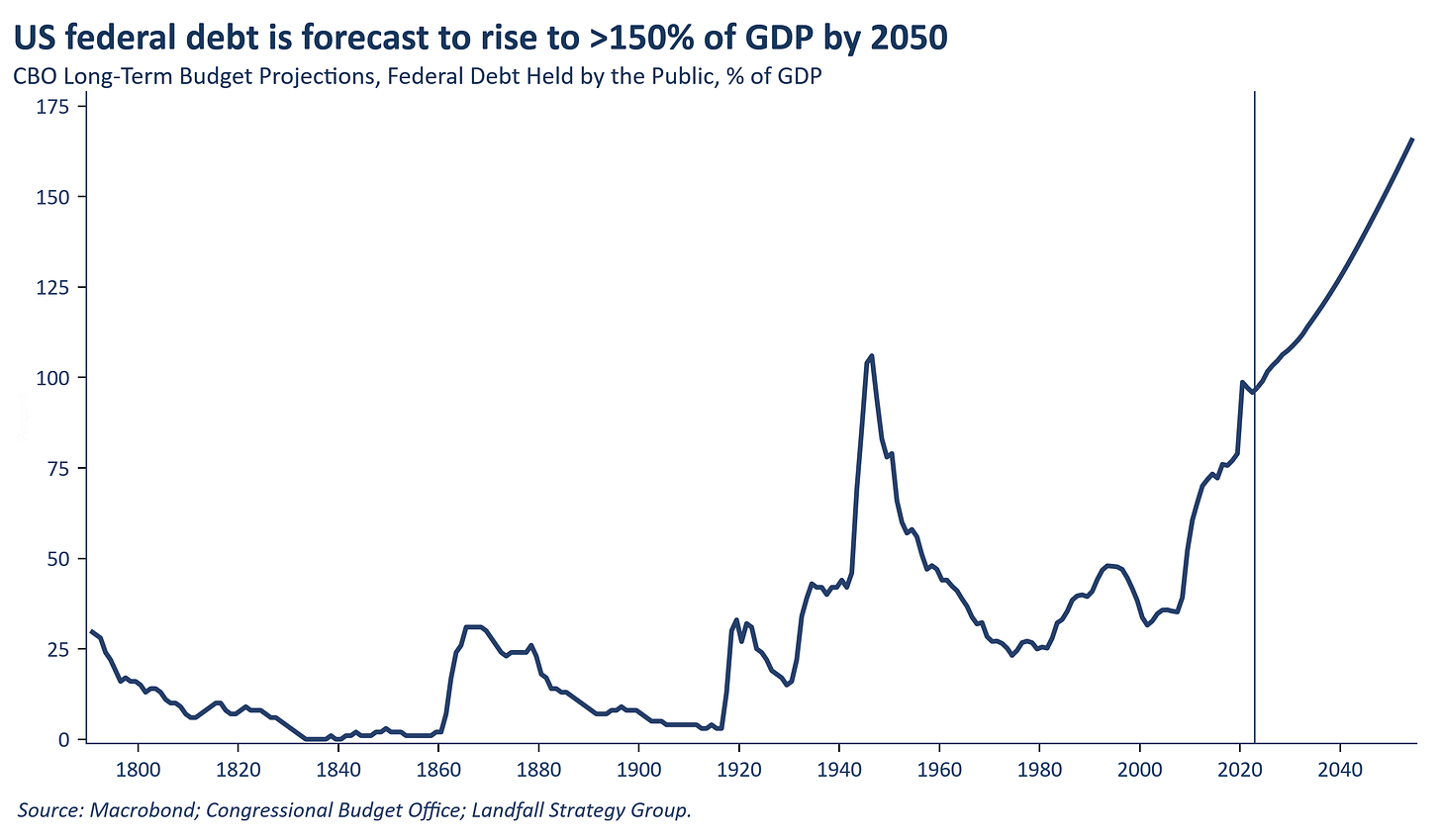

The US is also in uncharted fiscal territory. On Friday, the US Treasury reported a deficit of US$1.8 trillion for fiscal year 2024 (a record outside the pandemic), amounting to ~6% of GDP, despite strong growth and low unemployment. Public debt is approaching 100% of GDP. The official projections (from the CBO) estimate public debt >120% of GDP by 2034 and >150% by 2050. And the policy commitments of both Presidential candidates (and the mood of the Congress) is for further increased public debt.

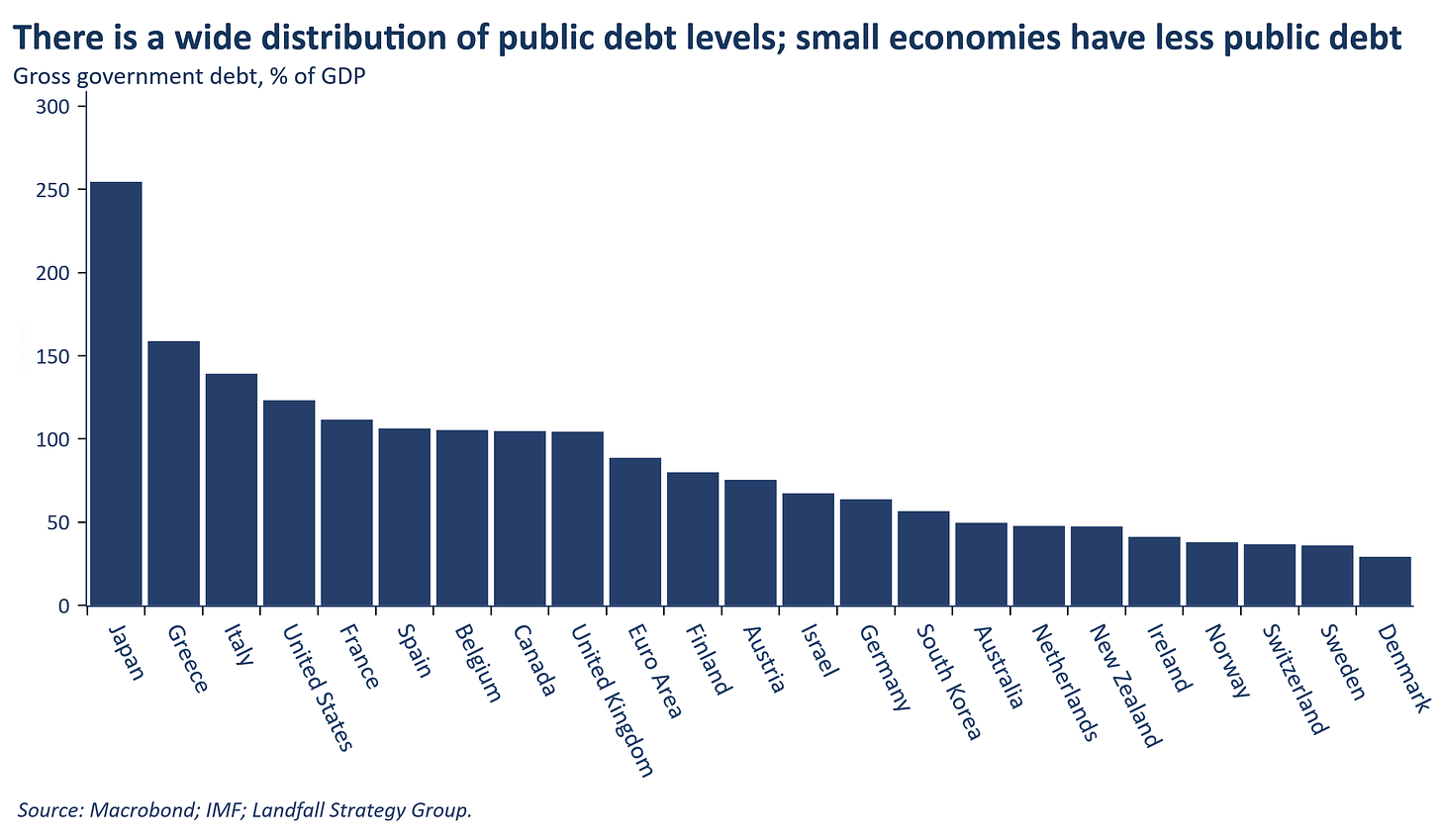

Different countries have different amounts of fiscal space, and are differently exposed to fiscal stress. The US, despite its parlous fiscal state, is buffered from a fiscal shock by its reserve currency status and its relatively high growth rates. European countries do not have these advantages, and face difficult judgements as they contemplate financing options for the massive increase in investment that the recent Draghi report recommended.

Markets have so far been relaxed about government debt, absorbing significant debt issuance. But non-linearities abound, and market pricing may change quickly.

'How did you go bankrupt? Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly', in Ernest Hemingway’s ‘The sun also rises’

Earlier this week, the IMF’s latest Fiscal Monitor estimated that global public debt was around US$100 trillion and that it would breach 100% of world GDP by the end of the decade (and cheerfully warned that the fiscal outlook is likely worse than this). This represents a source of global economic risk in a more turbulent world with an increased frequency of global economic and political shocks. A highly leveraged global economic system will be less well-placed to respond to major shocks.

This fiscal situation will also have geopolitical implications. To compete, countries will need to mobilise capital for investment: to invest in technology, supply chains, as well as hard power. This will require government investment as well as private capex. Fiscally constrained governments will be at a competitive disadvantage.

Indeed, high levels of public debt have often been a predictor of the fall of great powers. Note that the US government now spends more on debt servicing than on defence. And China is also heavily indebted: total debt/GDP is higher for China than for the US and faces significant debt challenges. The ability of governments to manage their balance sheets will shape the terms of geopolitical rivalry.

My in-depth client notes over the past month have provided insights into public debt dynamics across advanced economies, China’s weakening economic outlook, and developments in global trade flows. And my client briefings have discussed issues such as the implications of the US elections, geopolitics and technology, and the global macro outlook.

Get in touch (david.skilling@landfallstrategy.com) if you would like to discuss a trial to access these briefings and research.

To receive my free notes on global economic & geopolitical issues, subscribe here:

If you liked this note, do forward it - or share it with your network:

You can also connect with me on LinkedIn.